Here is a true story that illustrates that how we look at things makes all the difference in the world. A grandmother and grandfather are arguing over some petty matter. Unexpectedly, their young grandson — who has a life-threatening illness — points at the moon and says, “Don’t be mad, there is a happy moon in the sky tonight.” His words transform everyone’s outlook.

The power of reframing

Reframing is one of the most powerful techniques we have when it comes to dealing with challenges. My nephew was diagnosed with CF shortly after he was born. It’s a devastating disease. Treatments have gotten better, but in the past, the prognosis was usually very poor — very few children with the condition made it into their 20s.

Initially, the diagnosis was overwhelming. However, the doctors made one important suggestion: they said CF could either be in the driver’s seat or the passenger’s seat. That little bit of advice helped our family reframe the issue. We’d focus on helping this young person live fully. Battling a disease was still part of the equation, but it would take a back seat to life.

That mind-shift helped everyone keep a positive outlook. Thankfully, medical advances have occurred in the interim, which have greatly improved this young person’s situation. But I believe the initial reframing was pivotal too — it helped our family get to where we are now, which is a much better place.

Reframing in business

Here’s another story that illustrates how empowering reframing can be. In 1912, Teddy Roosevelt was running for president. The candidate was in the midst of a nationwide train tour to promote his candidacy and three million brochures were printed to advertise the occasion. There was just one problem — the pamphlet contained an impressive photo of Roosevelt, but underneath it was a little fine print accompanying the picture: “Copyright Moffett Studios, Chicago.”

Roosevelt’s campaign manager, George Perkins, soon realized he had a potentially huge legal and financial problem on his hands. The going rate for using copyrighted images was about one dollar every time it was used. That meant Roosevelt’s campaign could be liable for about three million dollars for using Moffett’s picture in their brochures.

From a conventional view, the choices seemed bleak. If Moffett Studios insisted on the copyright fee, then Roosevelt’s campaign would be bankrupt. However, ignoring the copyright issue altogether risked a major legal and ethical scandal.

Campaign manager George Perkins managed to reframe the issue as an opportunity. Employing some out-of-the-box thinking, he had his stenographer draft a letter to Moffett Studios that read:

“We are planning to distribute millions of pamphlets with Roosevelt’s picture on the cover. It will be great publicity for the studio whose photograph we use. How much will you pay us to use yours? Respond immediately.”

Moffett replied, “We’ve never done this before, but under the circumstances, we’d be pleased to offer you $250.” Perkins immediately accepted Moffett’s suggestion without asking for more.

Perkin’s approach to his dilemma is a classic example of reframing. Essentially, he interpreted a problem not as an obstacle, but as an opportunity. In particular, he refused to settle for the conventional either-or options that seemed to be the only ones available. Instead, he used his creativity and imagination to devise an entirely novel way of dealing with the situation.

Very often, we cannot change the objective features of a situation. But we can change our mindset. Interestingly, it’s this very shift in our outlook or perspective that allows us to transcend our initial challenge or problem.

Reframing with kids

Here’s a true story about reframing and kids. I’m sure many parents with young children will relate to this story, which involves getting two toddlers and one kindergartner to calm down during a car ride.

One day, I had agreed to accompany my sister as she took a long drive with her three kids to a doctor’s office well out of town. I was along on the ride mostly for moral support and so that my sister didn’t feel totally outnumbered by the kids in the car.

The first leg of the journey went remarkably well, though my 5-year-old nephew was clearly quite observant about the length of the trip. “Are we there yet?” and “How much longer?” are phrases I’m sure he uttered several times.

The doctor’s visit was routine and all went well, but as we started to pack the kids back in the car for the return trip it was clear that the children were started to get cranky. That’s when my sister started using some “if, then” logic on my nephew. “If you are good in the car, then maybe we can get a treat on the way back.” “If you don’t behave in the car, then I’ll have to tell your dad when we get home.”

I’m all in favor of reasoning with children, but in this instance the “if, then” logic seemed to be wearing thin — even backfiring — after a while

I could tell my sister was getting a little exasperated. As a result, I decided to try a slightly different variation on the “if, then” approach. “If you are not good,” I playfully told my nephew, “then your Uncle Scott will have to walk all the way home.” I could see his eyes light up as he followed the unexpected twist in logic. “Okay,” he said, with a big smile on his face.

The implications of my logical exercise were a little perverse. My nephew could misbehave, but I’d pay the price. It’s not a lesson I’d seriously want to impart. But in this instance, my little joke seemed to change the dynamic for the rest of the car ride. “If you’re not good, then there will be no pizza or ice cream later for Uncle Scott.” The atmosphere shifted from tense to happy and we enjoyed a safe ride home. Incidentally, it was one episode in my life where my degree in philosophy actually came in handy!

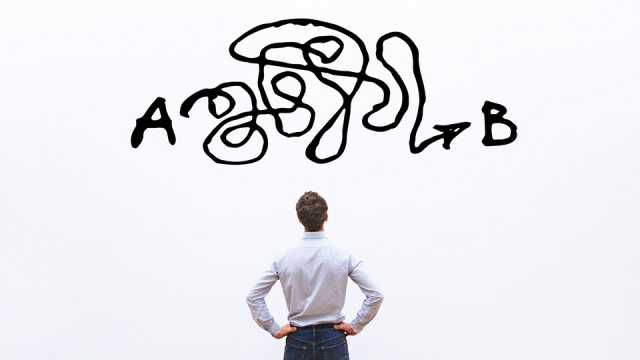

Sometimes, conventional habits of thought are so ingrained that our problems become like quicksand — the harder we try to solve them with traditional methods the worse things get. When that happens, try taking a deep breath or do something that will help clear your mind. Then, see if there isn’t some way you can creatively reframe the challenge.

— Scott O’Reilly